Circulatory system disorders involve the heart and blood vessels. Many signs apparently occurring in other systems (eg, dyspnea, indigestion) can be caused by heart disease. Conversely, signs often associated with cardiovascular disease (eg, peripheral edema) may be caused by disorders in other systems. Thus, all clinicians, not just cardiologists, must be alert for circulatory system disorders.

Circulatory System

-

Hematopoietic System Introduction

-

Anemia

-

Blood Groups and Blood Transfusions

-

Blood Parasites

-

Canine Lymphoma

-

Erythrocytosis and Polycythemia

-

Hemostatic Disorders

-

Leukocyte Disorders

- Overview of Leukocyte Disorders

-

-

- Numerical Abnormalities:

- Morphologic Abnormalities:

-

Specific Interpretative Leukogram Responses

- Corticosteroid-induced or Stress Response:

- Excitement or Epinephrine Response:

- Inflammatory Response:

- Combined Corticosteroid-induced and Inflammatory Response:

- Lymphocytosis:

- Lymphopenia:

- Stem-cell Injury and Pancytopenia:

- Eosinophilia and Basophilia:

- Prominent Metarubricytosis:

- Hematopoietic Cell Neoplasia and Leukemia:

-

Lymphadenitis and Lymphangitis

-

Cardiovascular System Introduction

-

Congenital and Inherited Anomalies of the Cardiovascular System

-

Overview of Congenital and Inherited Anomalies of the Cardiovascular System

- Outflow Tract Obstructions

-

-

- Coarctation of the Aorta

- Left-to-Right Shunts

-

-

-

- Right-to-Left Shunts (Cyanotic Heart Disease)

-

- Other Cyanotic Heart Diseases

- Conditions of the Atrioventricular Valves

-

-

-

- Vascular Ring Anomalies

- Persistent Right Aortic Arch

- Miscellaneous Congenital Cardiac Abnormalities

-

-

Heart Disease and Heart Failure

- Overview of Heart Disease and Heart Failure

-

-

-

-

Heartworm Disease

-

Bovine High-Mountain Disease

-

Thrombosis, Embolism, and Aneurysm

Circulatory System Sections (A-Z)

Anemia

Anemia is defined as an absolute decrease in the red cell mass as measured by RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, and/or PCV. It can develop from loss, destruction, or lack of production of RBCs. Anemia is classified as regenerative or nonregenerative. With regenerative anemia, the bone marrow responds appropriately to the decreased red cell mass by increasing RBC production and releasing reticulocytes. With nonregenerative anemia, the bone marrow responds inadequately to the increased need for RBCs. Anemia caused by hemorrhage or hemolysis is typically regenerative. Anemia caused by decreased erythropoietin or an abnormality in the bone marrow is nonregenerative.

Blood Groups and Blood Transfusions

Blood groups are determined by genetically controlled, polymorphic, antigenic components of the RBC membrane. The allelic products of a particular genetic locus are classified as a blood group system. Some of these systems are highly complex, with many alleles defined at a locus; others consist of a single defined antigen. Blood group systems, in general, are independent of each other, and their inheritance conforms to Mendelian dominance. For polymorphic blood group systems, an animal usually inherits one allele from each parent and thus expresses no more than two blood group antigens of a system. An exception is in cattle, in which multiple alleles, or “phenogroups,” are inherited. Normally, an individual does not have antibodies against any of the antigens present on its own or against other blood group antigens of that species’ systems unless they have been induced by transfusion, pregnancy, or immunization. In some species (people, sheep, cattle, pigs, horses, cats, and dogs), so-called “naturally occurring” isoantibodies, not induced by transfusion or pregnancy, may be present in variable but detectable titers. For example, Group B cats have naturally occurring anti-A antibody. Also, circulating antibodies to animal blood group antigens may be induced by transfusion. With random blood transfusions in dogs, there is a 30%–40% chance of sensitization of the recipient, primarily to blood group antigen DEA 1, but risk is also present for development of antibody to any other antigen lacked by the recipient. In horses, transplacental immunization of the mare by an incompatible fetal antigen inherited from the sire may occur. Immunization also may result when some homologous blood products are used as vaccines (eg, anaplasmosis in cattle). In dogs, prior pregnancy does not result in sensitization of the bitch to foreign blood group antigens.

Blood Parasites

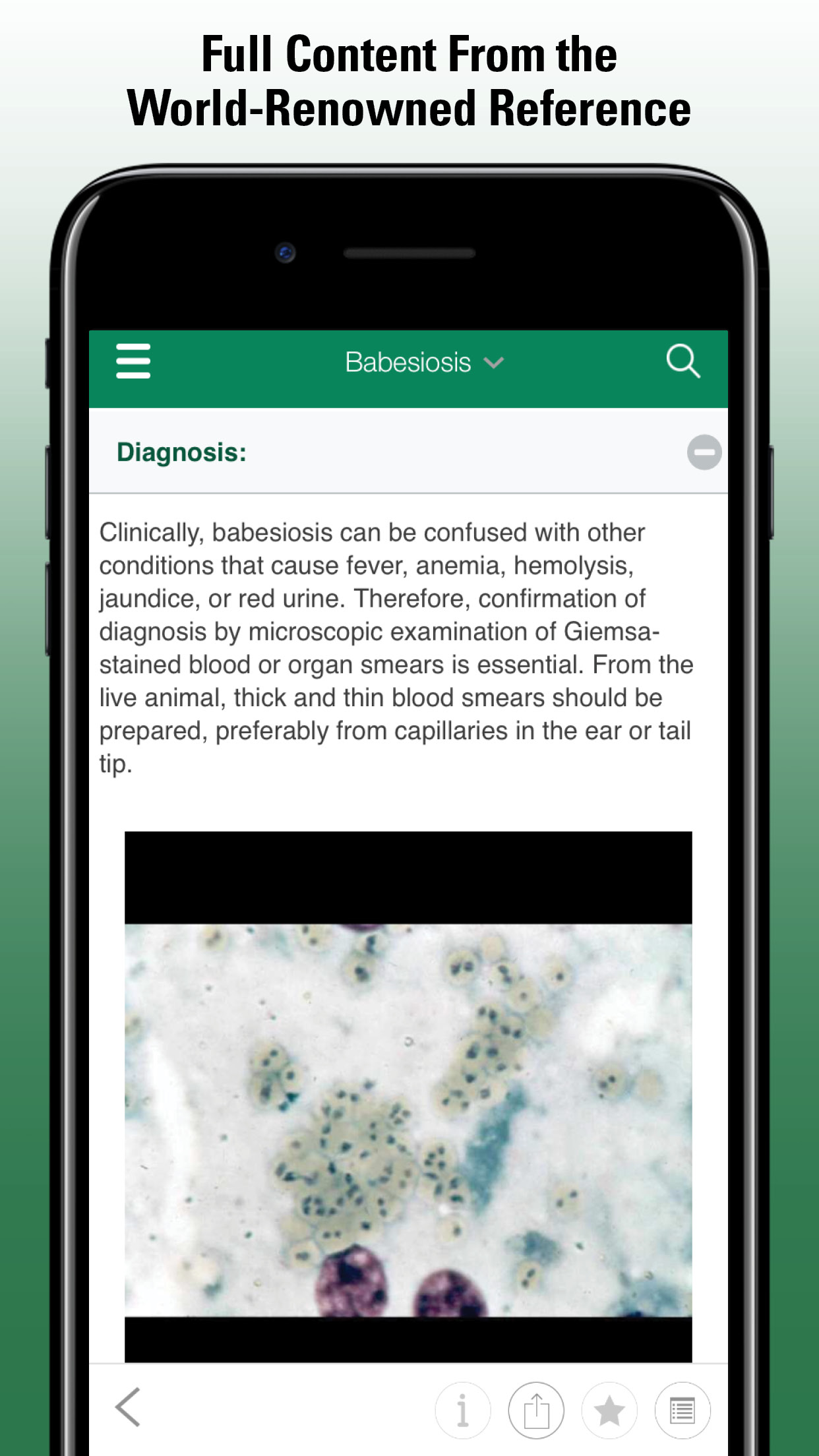

Anaplasmosis, formerly known as gall sickness, traditionally refers to a disease of ruminants caused by obligate intraerythrocytic bacteria of the order Rickettsiales, family Anaplasmataceae, genus Anaplasma. Cattle, sheep, goats, buffalo, and some wild ruminants can be infected with the erythrocytic Anaplasma. Anaplasmosis occurs in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide (~40°N to 32°S), including South and Central America, the USA, southern Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia.

Bovine High-Mountain Disease

Bovine high-mountain disease (BHMD) is characterized by a noncontagious swelling of edematous fluid in the ventral parasternal muscles (brisket region), the ventral aspect of the body including the abdomen, and the submandibular region in cattle raised in high-altitude regions (>5,000 ft [1,524 m]) in the western USA most commonly and substantially affecting Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Utah. It also affects cattle in mountainous ranges of the world, most commonly at elevations >6,500 ft (1,981 m) in western Canada and South America. BHMD affects cattle of all ages and breeds, but not necessarily equally.

Canine Lymphoma

Canine lymphoma is a disease term comprising a heterogeneous group of malignancies with varying biologic aggressiveness derived from the uncontrolled and pathologic clonal expansion of lymphoid cells of either B- or T-cell immunophenotype. Although neoplastic transformation of lymphocytes is not restricted to specific anatomic compartments, canine lymphoma most commonly involves organized primary and secondary lymphoid tissues, including the bone marrow, thymus, lymph nodes, and spleen. In addition to these lymphoid-rich organs, extranodal sites affected by lymphoma include the skin, intestinal tract, liver, eye, CNS, and bone. Lymphoma is reported to be the most common hematopoietic neoplasm in dogs, with an incidence reported to approach 0.1% in susceptible dogs. Despite the prevalence of malignant lymphoma, the underlying causes for its development remain poorly characterized; however, advanced genetic studies have revealed that canine lymphoma can be molecularly distinguished and categorized into discrete groups that correlate with biologic aggressiveness. Hypothesized causes include retroviral infection with Epstein-Barr virus–like viruses, environmental contamination with phenoxyacetic acid herbicides, magnetic field exposure, chromosomal abnormalities, and immune dysfunction. With the completion of the dog genome, it is anticipated that genome-wide association studies will identify specific genetic and chromosomal signatures involved in the pathogenesis of lymphoma.

Cardiovascular System Introduction

The cardiovascular system comprises the heart, the veins, and the arteries. The atrioventricular (mitral and tricuspid) and semilunar (aortic and pulmonic) valves keep blood flowing in one direction through the heart, and valves in large veins keep blood flowing back toward the heart. The rate and force of contraction of the heart and the degree of constriction or dilatation of blood vessels are determined by the autonomic nervous system and hormones produced either by the heart and blood vessels (ie, paracrine or autocrine) or at a distance from the heart and blood vessels (ie, endocrine).

Congenital and Inherited Anomalies of the Cardiovascular System

Congenital anomalies of the cardiovascular system are defects that are present at birth and can occur as a result of genetic, environmental, infectious, toxicologic, pharmaceutical, nutritional, or other factors or a combination of factors. For several defects, an inherited basis is suspected based on breed predilections and breeding studies. Congenital heart defects are significant not only for the effects they produce but also for their potential to be transmitted to offspring through breeding and thus affect an entire breeding population. In addition to congenital heart defects, many other cardiovascular disorders have been shown, or are suspected, to have a genetic basis. Diseases such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, and degenerative valvular disease of small breeds of dogs may have a significant heritable component.

Erythrocytosis and Polycythemia

Heart Disease and Heart Failure

Heart disease is defined as any functional, structural, or electrical abnormality of the heart. It encompasses a wide range of abnormalities, including congenital abnormalities (see Congenital and Inherited Anomalies of the Cardiovascular System) as well as anatomic and physiologic disorders of varying causes. Heart disease can be classified by various characteristics, including whether the disease was present at birth or not (eg, congenital or acquired), cause (eg, infectious, degenerative, genetic or heritable), duration (eg, chronic or acute), clinical status (eg, left heart failure, right heart failure, or biventricular failure), by anatomic malformation (eg, ventricular septal defect), or by electrical disturbance (eg, atrial fibrillation, ventricular premature complexes).

Heartworm Disease

Hematopoietic System Introduction

Blood supplies cells with water, electrolytes, nutrients, and hormones and removes waste products. The cellular elements supply oxygen (RBCs), protect against foreign organisms and antigens (WBCs), and initiate coagulation (platelets). Because of the diversity of the hematopoietic system, its diseases are best discussed from a functional perspective. Function may be classified as either normal responses to abnormal situations (eg, leukocytosis and left shift in response to inflammation) or primary abnormalities of the hematopoietic system (eg, pancytopenia from marrow failure). Furthermore, abnormalities may be quantitative (ie, too many or too few cells) or qualitative (ie, abnormalities in function). (Also see The Biology of the Immune System.)

Hemostatic Disorders

Effective hemostasis depends on an adequate number of functional platelets, an adequate concentration and activity of plasma coagulation and fibrinolytic proteins, and a normally responsive blood vasculature. The diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of hypo- and hypercoagulable animals is difficult with regard to both progression of disease and monitoring blood component and/or anticoagulation therapy. Citrated plasma samples are often used in veterinary medicine to determine fibrinogen concentration, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), prothrombin time (PT), and d-dimer or fibrinogen degradation product (FDP) concentration. The introduction of the cell-based, tissue factor (TF)/Factor VII–dependent model of hemostasis has increased understanding of the complex biochemistry of physiologic hemostasis, leading to reevaluation of the traditional understanding of physiologic hemostasis divided into the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways of coagulation. Although citrated plasma contains many of the factors involved in coagulation, whole blood contains both the soluble factors and intravascular cells active in physiologic and pathologic hemostasis, incorporating TF and phospholipid-bearing cells, such as platelets and leukocytes.

Leukocyte Disorders

Leukocytes, or WBCs, in the blood of healthy mammals include segmented neutrophils, band neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils. Abnormal leukocytes include neutrophils less mature than bands (eg, metamyelocytes, myelocytes, progranulocytes), blast cells of any hematopoietic lineage, mast cells, and other neoplastic cells. WBCs vary in their site of production, their duration of circulation, and the stimuli that affect their release into and migration out of the vascular system. Differences in leukocyte physiology account for species differences in normal blood cell concentrations and their responses in disease.

Lymphadenitis and Lymphangitis

Caseous lymphadenitis (CL) is a chronic, contagious disease caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Although prevalence of CL varies by region and country, it is found worldwide and is of major concern for small ruminant producers in North America. The disease is characterized by abscess formation in or near major peripheral lymph nodes (external form) or within internal organs and lymph nodes (internal form). Although both the external and internal forms of CL occur in sheep and goats, the external form is more common in goats, and the internal form is more common in sheep. Economic losses from CL include death, condemnation and trim of infected carcasses, hide and wool loss, loss of sales for breeding animals, and premature culling of affected animals from the herd or flock. Once established on a farm or region (endemic), it is primarily maintained by contamination of the environment with active draining lesions, animals with the internal form of the disease that contaminate the environment through nasal discharge or coughing, the ability of the bacteria to survive harsh environmental conditions, and lack of strict biosecurity necessary to reduce the number and prevent introduction of new cases. Although CL is typically considered a disease of sheep and goats, it also occurs more sporadically in horses, cattle, camelids, swine, wild ruminants, fowl, and people. Because of its zoonotic potential, care should be taken when handling infected animals or purulent exudate from active, draining lesions.

Thrombosis, Embolism, and Aneurysm

A thrombus is an aggregation of platelets and fibrin that may form when certain conditions exist. Historically, these have included some combination of Virchow's triad such as blood stasis (reduced flow), endothelial injury, and/or an existing hypercoagulable state. A thrombus can develop in a cardiac chamber and be attached (mural) or less likely free floating (ball), or can originate in situ within a blood vessel where it can cause a partial or complete obstruction. The thrombus can be classified based on its location and the clinical signs it produces (eg, jugular venous thrombosis in large animals associated with prolonged venous catheterization, pulmonary arterial thromboembolism associated with heartworm disease in dogs).

Also of Interest

Test your knowledge

A 10-year-old, male-castrated golden retriever has a 1-month history of mild lethargy and decreased appetite. On physical examination, he has pale mucous membranes and weak femoral pulses. His complete blood count (CBC) shows a decreased packed cell volume (PCV), decreased mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and decreased mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC). His biochemistry panel shows a mildly increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level and mildly increased serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level. Which of the following is the most likely cause of this dog’s anemia?